OPINION: The death of swing state Ohio

Photo via: The White House/Public domain/Wikimedia Commons

Though his nationwide win in 2016 took many by surprise, President-elect Donald Trump’s first victory in Ohio was less shocking.

Ohio was known for being a bellwether state; having correctly chosen the President in 1964 and every election since then. In 2020, for the first time in decades, Ohio cast its 18 electoral votes for the losing candidate.

Rather than fluctuating, Ohio had declared its loyalty for the Republican. It seemed like our days as a battleground state might be over.

Glimmers of swing state Ohio remained as Ohioans turned out for down-ballot races in the coming years. The 2016 Ohio that had embraced Trump re-elected Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown to a third term in 2018. In 2023, voters passed progressive ballot initiatives protecting abortion access and legalizing recreational marijuana.

What Ohio saw last week, though, was nothing short of a red wave. Donald Trump won the state for a third time. Ohioans rejected Issue 1, Ohio’s anti-gerrymandering redistricting issue, by a seven-point margin. Republicans won all three state Supreme Court races, securing a 6-1 conservative majority on the high court.

Perhaps most notably, voters denied Senator Brown another term, electing car salesman Bernie Moreno.

Why did Ohio break its decades-long streak to support Trump in 2020, when most Americans rejected him? And why did Ohioans oust Sherrod Brown after electing him not once, but three times?

My search for answers took me to a cluster of counties concentrated in Ohio’s northeasternmost corner and along the shores of Lake Erie.

The former blue counties of the Northeast

To Mack Carrasquillo, Lorain County represents the heart of America.

Carrasquillo grew up attending school in North Ridgeville, Ohio, about half an hour’s drive from the southern shores of Lake Erie. Later, he attended high school in Elyria and earned an associate’s degree at Lorain Community College before coming to Ohio University, where he’s pursuing degrees in organizational communication, international studies and Appalachian studies.

“You’re talking about people who’ve come from all over the world,” Carrasquillo said. “Most of them from Latin American countries and regions, specifically [the] Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico. Then we also have large Croatian communities, large Slovakian, Czechoslovakian communities, Macedonia, Hungary…”

These immigrants came to Lorain County to work in steel mills in the Cleveland area, many of which are no longer in operation, Carrasquillo said. “But there’s still that strong Midwest work ethic point of view.”

Where divisions exist, Carrasquillo says, they exist along ethnic and socioeconomic lines. In predominantly white areas like North Ridgeville, Avon, Avon Lake and Grafton, “you see people saying, I will never go to Elyria, because it’s unsafe,” Carrasquillo said. “It’s interesting because North Ridgeville is right on the border of Elyria.”

But when it comes to politics, Carrasquillo says Lorain County is 50/50.

In 2016, he said, many people saw Donald Trump as a voice for lower-class Americans and therefore for Lorain County. “But that’s not Lorain County in its entirety,” Carrasquillo said. “That’s what makes it a 50/50 place.”

That year, Hillary Clinton won Lorain County by less than 1,000 votes. Four years later, Trump won the county by a slightly larger margin of around 4,000, becoming the first Republican candidate to do so since 1988.

A junior at Ohio University, who grew up in Elyria and chose to remain anonymous, pointed to people around them who switched party affiliations or split their tickets. “My father is a blue-collar worker who voted for Obama and then Trump, as well as a number of his work friends,” the student said. In addition, several people they knew split their tickets in the 2024 Ohio Senate race, simultaneously supporting Moreno and Vice President Kamala Harris.

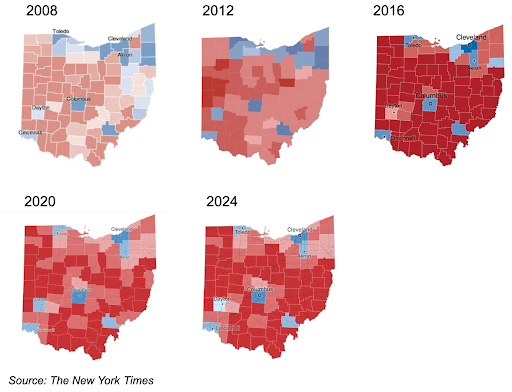

When Obama took Ohio for the first time in 2008, he won a total of 22 counties, most of them concentrated along the state’s northern and eastern borders.

With each election that followed, Democrats’ hold on northern counties grew weaker. In 2016, Hillary Clinton lost Ashtabula, Erie, Portage, Sandusky, Trumbull, and Wood.

Now, in 2024, Ohio’s blue counties are islands in a sea of red. Of Ohio’s 88 counties, Kamala Harris won only seven.

Brown’s 2024 loss can be attributed to a similar set of counties. Moreno took eight counties — Wood, Ottawa, Erie, Lake, Portage, Ashtabula, Trumbull, and Mahoning — that Brown had won in 2018.

This trend raises the question: why do northeast counties vote as a bloc? And why did Democrats lose their hold on that bloc?

Understanding the Northeast: Youngstown, Ohio

“They’re all coming back.”

These were the words of President Donald Trump when he came to Youngstown in the summer of 2017.

Less than two months later, Sept. 19th, 2017 would mark the 40th anniversary of Youngstown’s infamous “Black Monday” — a day widely associated with the beginning of the Mahoning Valley steel industry’s rapid collapse.

In the 20th century, the Mahoning Valley was the second-largest steel-producing region in the country. Steel production in America reached its peak in 1973. But in 1977, Youngstown Sheet and Tube announced the closure of its Campbell Works Mill, which employed roughly 5,000 people. Five years later, 50,000 jobs had disappeared from the Valley.

Since then, industry has been at the center of many political campaign promises to Youngstown. Ronald Reagan toured the shut-down steel mills in October 1980 and criticized the Environmental Protection Agency, seeming to blame environmental regulations for the industry’s decline.

In his first two years in office, Obama visited Youngstown three times to take credit for the success of a new V&M Star plant, even naming the city in his 2013 State of the Union address. When Obama retained the support of Mahoning County in the 2012 election, it seemed he had kept its trust.

Then came Trump. Understanding Trump’s appeal to the Mahoning Valley perhaps requires an understanding of one of Youngstown’s most beloved political figures.

Zachary Miller, who described himself as a former “blue dog Democrat” and present-day “Trump Democrat”, spent much of his life in Youngstown before moving to Fort Myers, Florida. Miller said Trump reminded him of Jim Traficant.

Traficant, a Democrat known for his catchphrase, “beam me up, Mr. Speaker,” served nearly 20 years in the House of Representatives before becoming the second member of Congress to be expelled from the House since the Civil War.

“The area’s anti-establishment electorate cheers politicians who ruffle feathers, and brushes off criminal activity – even prison time like that which Traficant served for taking bribes and kickbacks – as a cost of doing business,” journalist Julie Carr Smyth wrote in The Morning Journal, a newspaper based in Lorain, Ohio.

The road ahead for Democrats

With three consecutive Trump victories now in the books, it will be easy for Democrats to label Ohio a lost cause.

In the wake of Trump’s victory last week, pundits, politicians, and academics have wasted no time scrambling for answers to the question many are left wondering: where did Democrats go wrong?

Some have labeled the 2024 election a rebuke of the Democratic Party. With Republicans now in control of all three branches of the government, it’s hard to deny that, but it’s important not to conflate rejection of the Democratic Party with a rejection of progressive policies.

By pinning the blame on voters, Democrats reject the notion that the vast majority of Americans are rational actors motivated by a desire to better their standards of living, rather than by malice. Whether Trump truly represents the interest of the voters he claims to care about is irrelevant; he’s successfully sold voters his vision for America, while Democrats have failed to do so effectively.

In swing counties like Mahoning, voters have proven that what they’re looking for in their candidate, liberal or conservative, is someone who goes against the grain. Democrats won’t earn the trust of those voters by continuing efforts to moderate and attempting to open up the big tent party to moderate Republicans.

If Democrats can prove themselves capable of regaining that trust, they’ll do it by running candidates who color outside the lines. They’ll do it by building a platform of clear and specific policy goals, rather than vague, idealistic language. They’ll do it by offering a vision for America that’s exciting, affirmative, and fresh.

Please note that these views and opinions do not reflect those of The New Political.