Who is Deb Shaffer? A quest for the elusive mind behind a university’s budget

Art by Emily Crebs.

Editor’s Note: This story is written as a first person narration of a reporter’s investigation to learn more about Deb Shaffer, the chief financial officer at Ohio University. The reporter felt that writing the story this way would be the most honest, as she is a student at Ohio U. It includes her perspective as an investigator.

Editor’s Note: This story was updated with the correct county of Shaffer’s residence in Florida. A previous version of this story listed it as Orange, not Osceola.

As an Ohio University student, I’m comfortable with the general formula of promotional videos introducing students to campus. Current students, faculty, college deans and administrators are all likely to appear, giving students a name and face to latch on to when thinking of the “Bobcat Family.”

I feel as if I know President Duane Nellis as much as anyone can know the figurehead of a campus of thousands of students — his unassuming voice, his continued praise of the university and his tweets about fall leaves on College Green.

And yet, arguably the second most powerful person at the university seems to be a figment of Cutler Hall, a face never highlighted in university promos. I found it odd that her name rarely came up in university meeting stories where I could easily find “President Duane Nellis” or “Provost Elizabeth Sayrs.”

That person is Deborah Shaffer, the senior vice president for finance and administration and chief financial officer at Ohio U. Her duties include overseeing Ohio U’s finances and balancing the budget.

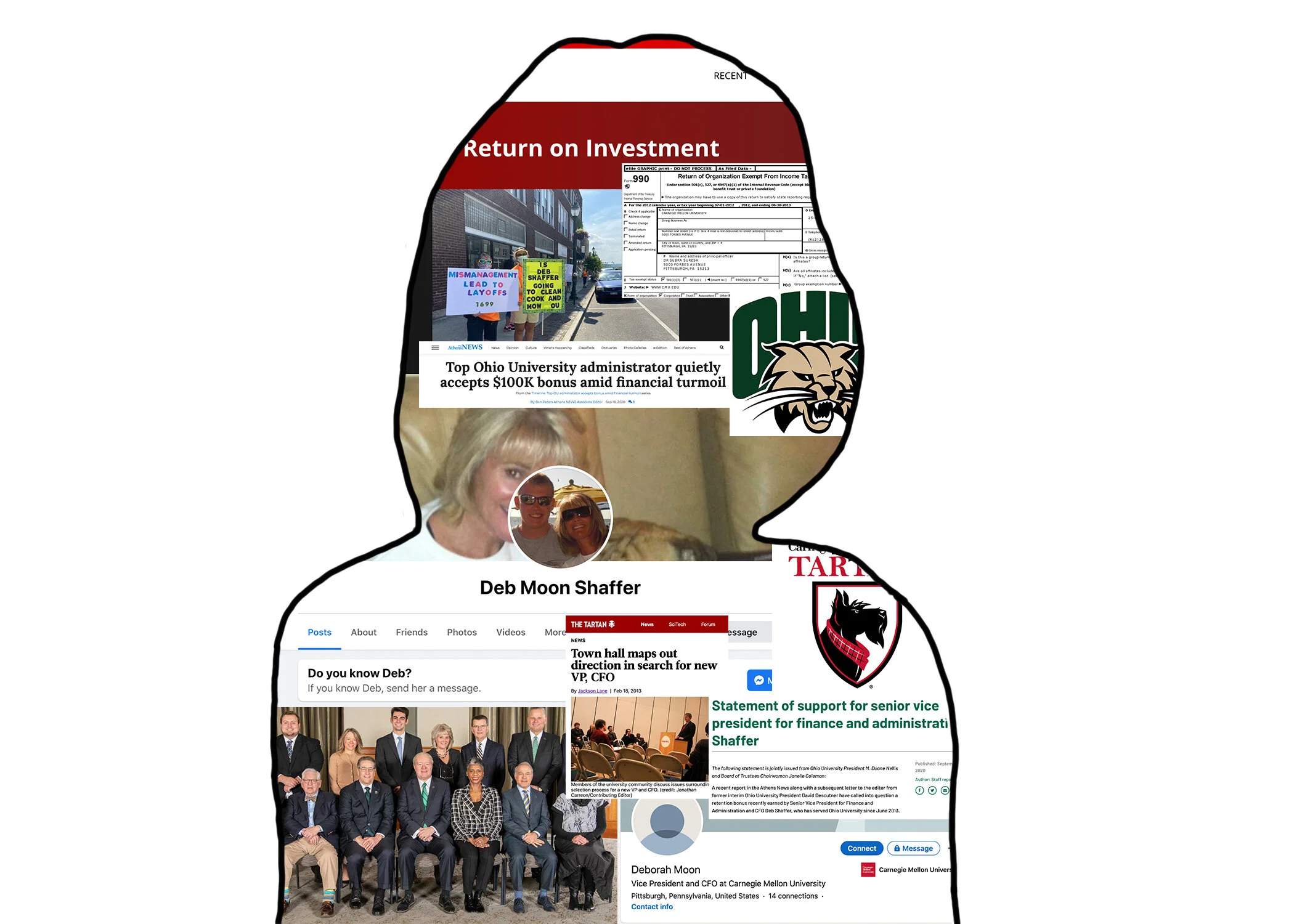

Shaffer’s name came into the limelight last fall when The Athens NEWS reported a story with the headline “Top Ohio University administrator quietly accepts $100K bonus amid financial turmoil” on Sept. 18. Since May 2020, more than 200 instructional faculty and administrators, 140 skilled-trade workers, and 81 clerical and technical employees have lost their jobs, the report said. Social media was sent ablaze with criticism for the timing of the layoffs and the bonus.

With the photo accompanying the article, I had an image to put with the name — not of Shaffer, but of a protester holding up a poster that read, “Is Deb Shaffer Going to Clean Cook and Mow OU?” But I still didn’t even know what Shaffer looked like.

Who is Shaffer? What is a CFO, and how did Shaffer come to be hired at Ohio U? Why would laid off faculty ask her to clean and mow? How didn’t she predict the enrollment declines that the university attributes to layoffs of employees?

I decided to find out. After all, it’s my money she’s managing.

On her biography webpage at Ohio U, Shaffer appears as a middle-aged woman with sandy blonde hair cut into a bob with bangs. In a photograph of the Ohio U Board of Trustees, she seems to be short in height, but perhaps that’s because she’s standing between two men taller than her. Now I had a face, but it wasn’t animated with knowledge of her history or personality.

I took to the best place to discover the character of a stranger in the digital age: Facebook.

I found a “Deb Moon Shaffer” profile and clicked on it. In the main profile picture, Shaffer is smiling with sunglasses on with a man I don’t recognize. She seems younger, as well as in the background photo, where she sits on a couch in a white sweatshirt with a wrinkly-faced dog wearing a tie-dyed shirt. The background image was set on Dec. 16, 2012.

While most Facebook accounts allow you to make a friend request, Shaffer’s didn’t have the option. But I learned the name “Moon,” which Shaffer may have used in her past. “Moon” would prove to teach me much about Shaffer’s professional life.

I went back to Google, looking up permutations of “Deborah,” “Deb,” “Moon” and “Shaffer.”

From LinkedIn, I confirmed that Shaffer has held the position of chief financial officer before, as well as a top position in finance and administration at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), located in the Oakland neighborhood of Pittsburgh, PA, for eight years.

According to Ohio U’s website, she came to Ohio U in 2013 and assumed the position of chief financial officer in 2016. While I can only guess what drew Shaffer to OU, I do know Shaffer’s Ohio U contract stipulates she would earn $306,000 a year, later updated to $327,726 and reduced to $294,953 during the coronavirus pandemic. She would earn a $100,000 retention bonus on June 30, 2020, and is set to earn an additional $100,000 retention bonus on June 30, 2023.

Adding “Carnegie Mellon University” provided a picture, albeit unfinished, of Shaffer’s life at CMU. Shaffer joined CMU in 2001 and was appointed CFO in 2005, according to the CMU website. She was named CFO of the Year by the Pittsburgh Business Times in 2008.

“Imagine overseeing the balance sheets of 600 small businesses, some overseas. That’s not too far from what Deborah Moon does as CFO of Carnegie Mellon University,” the article “Moon at center of CMU universe” in the Times reads, with glowing reviews from other administrators for Shaffer’s work.

While I couldn’t find a definition of the position “Chief Financial Officer” on Ohio U’s website, Investopedia defines the position as an individual who is responsible “for managing the financial actions of a company.” Through attending administrative meetings at Ohio U, I’ve learned that means managing Ohio U’s budget and projected budget by assessing actual and projected costs and revenues. That includes creating projections for enrollment and budgeting based upon those projections.

In the Q&A portion at the end of the Times article, Shaffer answered a few questions about her personal opinions of working as CFO.

She said what she liked best about her job was “the ability to learn every day. I’m surrounded by so many incredibly bright people who are experts in so many diverse fields … It’s just amazing to be with those types of minds and watch how they work and have access to them.”

Her biggest challenge, she said, was learning how to be effective in an academic environment rather than a corporate one.

“Education — it’s more of a shared governance. It’s not the (place) where you dictate rules. It’s more persuading people or encouraging them to follow the rules. You learn a different way to be effective,” Shaffer said in the Times article.

It appears that CMU adored Shaffer. Her heralds as CFO of the year in 2008 were followed a year later by an article titled “Return on Investment” in the Carnegie Mellon Today.

“Deborah Moon takes a deep breath and exhales, a subtle smile crossing her face as she deals with the whirlwind that is her 17-year-old teenage daughter. It’s early evening at a local mall and Carnegie Mellon’s CFO since 2004 is doing what she does best to get away from the daily gauntlet of conference calls, meetings and intensive investment analysis — she’s spending money,” the story reads.

If Shaffer was doing an excellent job of managing CMU’s money, why did she leave?

As CMU is a private institution, it did not comply with my public records request for Shaffer’s contract. In Google searches, however, I came across CMU’s Form 990 filed in 2012, a form filed annually by nonprofit institutions.

According to the form, Shaffer left CMU in October 2012 with severance benefits, additional compensation to an employee who is leaving a position, of $402,978 on top of her salary of $277,837.

Next, I scavenged CMU’s local and student media for any clues.

The Tartan, CMU’s student newspaper, reports in the story “Town hall maps out direction in search for new VP, CFO” that a search committee was established “following former chief financial officer Deb Moon’s departure in late 2012.”

The story did not list, however, a reason for Shaffer leaving. CMU’s public relations also did not return my request for an interview about Shaffer’s work at the university.

When Shaffer assumed the position of CFO in 2016, Ohio U had 36,867 students enrolled between the Athens, regional campuses and eLearning, according to data on the Ohio U website. In 2017, enrollment shrank overall to 36,215 students. It continued to decline each year after, with 33,044 students enrolled in 2019.

Ohio U has repeatedly cited the declining number of 18-year-olds graduating high school and enrolling in college as the cause for the financial situation.

Ben Bates, a professor at the Scripps College of Communication and vice president of Faculty Senate, said in a video interview the coronavirus pandemic is also contributing to recent declines in enrollment — and less money for Ohio U’s budget.

“We have fewer dollars to spend, [which] means we need to be really smart about where we’re going to spend those dollars,” Bates says.

Faculty would like some say in the allocations of resources, but this idea of shared governance Shaffer mentions in the Q&A was limited.

Doug Clowe, the chair for the finance committee of Faculty Senate, explained to me that while faculty have shared governance in some areas of the university, they do not in others.

“The only places where faculty get to make decisions is in matters directly involving the faculty,” Clowe said in a video interview.

Lack of communication from Shaffer and other university officials has only exasperated frustrations regarding the financial status of the university.

Faculty Senate invited Shaffer to attend the Nov. 2 virtual meeting and answer a set of questions provided in advance by the body. Shaffer did not show and only submitted her answers to the questions with links to outside sources.

“What we had hoped was she would read the questions holistically and say, ‘This is really a question about values and priorities, and I’ll explain that,’” Bates explained. “Unfortunately, for whatever reason, Deb Shaffer chose not to come to the Faculty Senate meeting that evening to answer us in person.”

Ohio U has a budget planning council, which Clowe serves on, and Joseph McLaughlin has ten years of experience serving on. But the council does not have a hand in the large budget decisions made at Ohio U any more than Faculty Senate does.

“I still don’t know, at the very highest levels of the university with the chief financial officer, the provost, the president, the athletic director, the head of student affairs, how decisions get made at the highest levels about budgets. That is a very, very, very opaque process,” McLaughlin told me in a phone interview.

While I didn’t expect to receive a warm welcome by CMU to my requests for information, I hoped Ohio U would be more willing. In an email sent to Ohio U’s Communications and Marketing, I asked for an interview with Shaffer, explaining that I wanted to share Shaffer’s side of the story as fairly as possible.

I was given a university statement instead, previously released to defend Shaffer when The Athens NEWS story about her bonus came out.

“Ms. Shaffer has been a strong and capable leader of the University for more than seven years, guiding the institution and the Board of Trustees through significant growth as well as times of financial challenge,” the statement read.

The statement, sent by Executive Communications Director Carly Leatherwood, also said it is important for Shaffer’s compensation and bonus “to be competitive in a national market.”

Leatherwood’s email ended with a statement that makes my heart sink: “We do not have further comment to offer at this time, and Ms. Shaffer has respectfully declined your interview request.”

Perhaps if there wasn’t a pandemic, I would have walked up to Cutler Hall to ask Shaffer for comment. But she might not even be there.

According to her property records for Meigs County, she sold her home on Dec. 16, 2020. I couldn’t confirm if she had bought more property within driving range of Ohio U, but I did find her property records for a house in Osceola County, Florida, perhaps where Shaffer is weathering out the pandemic.

I’m left with only the vague outlines of Shaffer that words on a computer screen can produce. Unlike a regular profile piece, I don’t know from her what it’s like in the daily life of a CFO at Ohio U, especially during a pandemic. I don’t know how she felt when The Athens NEWS story of her retention bonus broke and sent social media ablaze with criticism. I don’t know how she ended up in a small town in the foothills of Southeast Ohio instead of staying in the bustle of Pittsburgh.

In the end, my initial perception of Shaffer, however, has remained unchanged. Shaffer seems to have exclusive access and control in the room where it happens. She has access to information that the rest of us may never know, and neither Shaffer, nor Ohio U administrators, seem eager to share.