Skye Tafoya’s Ul’nigid’ – The basket book that carries stories

Photo via: Skye Tafoya

In honor of Indigenous Peoples’ Day and Ohio University’s library archives recent purchase of a copy of Rhiannon “Skye” Tafoya’s artist book, Ul’nigid’, The New Political’s Editor-in-Chief Jack Slemenda sat down for an exclusive interview with the Eastern Band Cherokee and Santa Clara Pueblo artist. Tafoya talked about the family history behind her book, what it's like being a full-time artist, how one of the 44 copies made it to Ohio U and the importance of family. For those interested in experiencing Ul’nigid’ in person click here for more information or email Ohio U library archivist Miriam Intrator: intrator@ohio.edu.

The artist and her art:

Rhiannon “Skye” Tafoya is an Eastern Band Cherokee and Santa Clara Pueblo artist who, “employs printmaking, digital design, and basketry techniques in creating her artist’s books, prints, and paper weavings. Both of her Tribal heritages, cultures, and lineages are manifested in her two- and three-dimensional artworks,” states Tafoya’s website.

Photo of Skye Tafoya from her personal website.

In 2020, Tafoya sat down to create 44 unique artist books bearing the title Ul’nigid’ (which translates from Cherokee as strong) in honor of her maternal grandmother, Martha Reed-Bark.

“She was the first figure I looked up to and learned from … Ul’nigid’ is a poetic narrative of my personal memories of her. I made this book with the intention of sharing the spirit and story of a traditional Cherokee medicine- woman/basket-weaver whose first language was Cherokee,” writes Tafoya. “She had a special role in my life, in my family and in my community, one that shouldn’t be forgotten.”

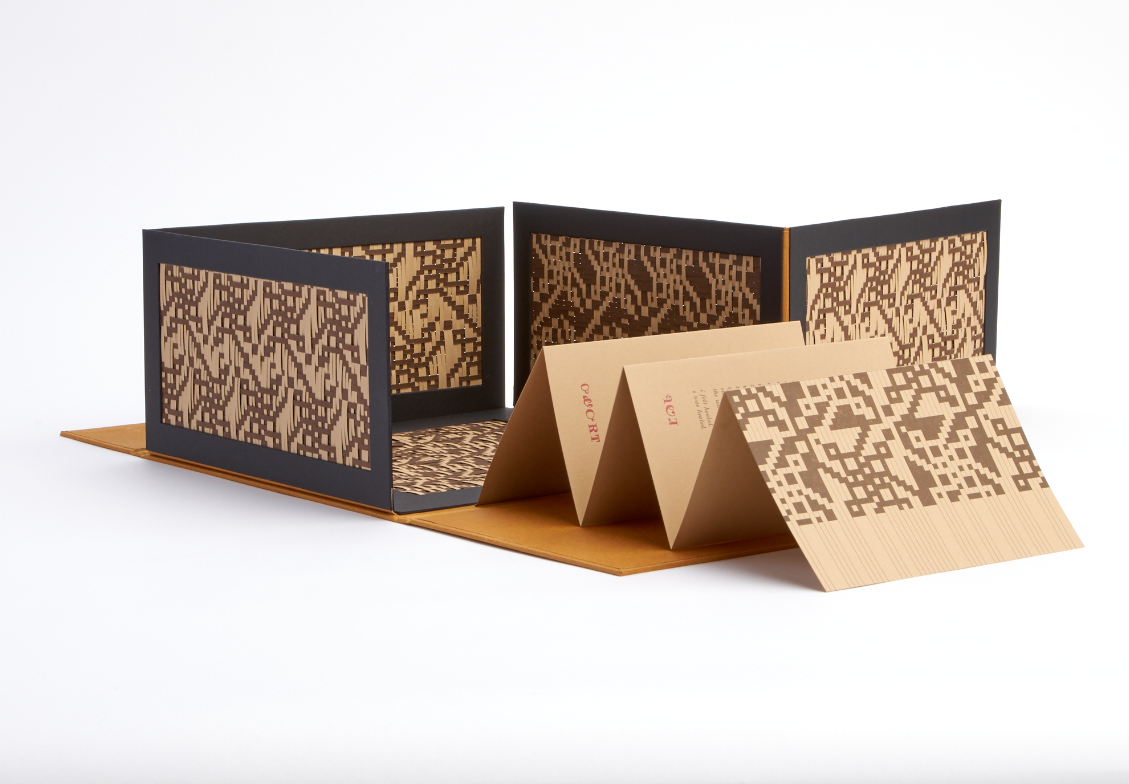

Once the reader completely unfolds the moveable book, walls form and the book can be left in a standing position similar to that of a basket.

Each weaving wall is Tafoya’s own design where she used, “weaving processes similar to those of a traditional Cherokee river-cane basket but were woven with paper instead of river-cane and white oak.”

“The design represents the energy of my Indigenous lineage as well as the urge to break out of boxes that a colonized society puts my identity, culture, and art into,” states Tafoya.

When the book is in basket form, an “accordion fold pamphlet” of five metal letterpress memory poems with Cherokee syllabary rests at the bottom. The poems serve as memories Tafoya has of her grandmother revolving around ideas like home, language, healing, love and lineage. When crafting the poems Tafoya also saw it as an opportunity to share her grandmother’s personality and life experiences with her son as she was pregnant during the creation of Ul’nigid’.

Photo via: Skye Tafoya

Before and after Ul’nigid’ Q and A:

Q: Can you tell me more about your family and what your upbringing means for your art?

A: After I had a kid, that definitely sparked a lot more themes within my art. However, I do come from a family of artists. My dad was really good at drawing faces and people, some of my cousins are illustrators, some painters, some clay artists. So, when I was a kid I had this older cousin named Darren who lived with my Granny and he used to draw so I’d sit there and draw a picture or two. That is really a core memory of mine that sparks inspiration even to this day, I think about him a lot. Even when I see him he is always so amped to see whatever I am working on and is such an inspiration. My brother and husband are also artists, so everyone is in it and I am happy that it’s like that.

Q: How did you decide to make art your full-time career?

A: I decided to take a painting course at this new college I went to and it just reset everything especially since I was studying sports medicine and I just didn’t understand sciences and that vernacular.

I eventually transferred to a Native art school called The Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico where I learned printmaking and bookbinding. Those mediums are so interesting to be with because there are so many opportunities within them and different directions that you can go and get such different results. Problem-solving is something that draws me to those mediums, you have to really think out everything beforehand but even when you do there are always mistakes. After I graduated II (Institute of American Indian Arts) you know life happens and it's not that easy to just fall into good job opportunities or something that fits with the things that you study for.

Well, that brought me to Nike retail for a long time. There was a point where I really wanted to design shoes and clothing so I did a transfer from the New Mexico store to the headquarters Beaverton store. I hoped that I could transition into like a design job there but it didn't work out that way and thankfully it didn't because design is super cool but there are a lot of parameters you have to be put in for your client base. You're not really making work for yourself you're always designing for somebody else.

After that, I went back to grad school and that was great. I studied letterpress, printmaking and screen making. But similarly to college, I graduated and was like ‘What the hell am I going to do now?’ I went on and worked with elderly people for a little bit but kept feeling like I had to work another job to fuel my art or apply for grants and that got tiring again.

Eventually, I got the residency grant at the Women's Studio Workshop in Rosendale, New York, and that whole experience completely changed my trajectory, as it allowed me to create Ul’nigid’. I learned I was pregnant while I was there and that transformed my whole way of creating and thinking. So, I really wasn’t working as a full-time artist until Ul’nigid’ was made in about 2020. I was about to give birth and that is when people actually started buying that book. It felt like such a gift from my family, from my Granny because I was able to provide for my unborn kid.

Q: How did Ohio University come into contact with you and your book?

A: Well, Women’s Studio Workshop has a very good relationship and repository with a lot of institutions because they publish a lot of artist books. So, when you make an artist book with them, 20% of the sales go to WSW and their budget, an extra 20% goes to general sales and the rest is completely up to the artist. At one point I was only making half of the profit on the books so I reached out to the studio and asked if I could have the books back and try and sell the books myself. Surprisingly, they agreed and were more than willing to let me do what I needed to do. This kind of worked, I cold-emailed a lot of people and sold some of the books. For Ohio University I think the people from the library got in contact with WSW. There were a lot of different places that my book went, some people saw it at book art fairs or they would see it in an expedition. I also submitted it for a book arts contest one time so people could have seen it there and then there is always word of mouth.

Q: What do you hope people take away from your book?

A: The value of family. The value of knowing who you come from. With my family, it is nice to know that I have a family of artists and I have a family of people who knew this landscape. My family really understands where they are from, even if it means from the earth. But the second thing I really like about Ul’nigid’ is that when they buy it from me I prefer that they are teaching with it. Having people touch and look at the book is the beauty behind book art. I hope that any student studying book arts is inspired to do something of their own design of making. There are a lot of book structures that someone invented at one point in time that people still use today, and that is fine. However, it is nice to reinvent it [book structures] at other times and try and get more creative with it instead of copying someone else’s design, that tells your own story. Ul’nigid’ was really important to me because it was a basket and my Granny is a basket maker and my dad is a basket maker. When I think about baskets they carry these stories and that is the same thing books do, they carry stories.